The Western Hero Deconstructed in The Searchers and A Fistful of Dollars (Essai comparatif en anglais)

|Italie - 1964|

In the mid-1950s and early 1960s, filmmakers began to

question the dichotomies and traditional narrative elements of the mythologized

west such as the “black hat, white hat” archetype. In this revisionist

tendency, traditional western heroes, like cowboys and cavalrymen, lose some of

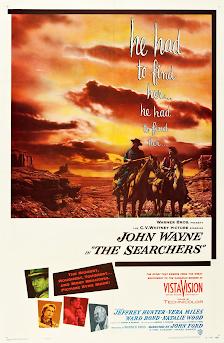

their lusters. In John Ford’s The Searchers, Ethan, the

protagonist, is one of the first to be blatantly racist in American westerns.

Meanwhile, in Italy, certain filmmakers propose an even more radical approach,

the spaghetti westerns. They reject almost all the values depicted in classical

westerns as naïve and propose a more cynical approach. I will argue that the

characters of Ethan Edwards in The Searchers and Joe in

Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars both dispute the

mythologized discovery of the west and question the heroic portrayal of the

western hero. I will begin with a discussion of the characters’ biases then

continue with their ethics and motivations.

Before the fifties, the first nations’ depiction in

Western films had remained mostly functional. With the forties, Hollywood

started depicting first nations realistically, or at least sympathetically,

often employing real natives. But it is only in the 1950s that filmmakers

started to question the validity of the “manifest destiny” mythology they had

empowered according to which Anglo-Saxon white Americans had a God-given right

to settle everywhere in America. This questioning echoes the anxiety regarding

the civil rights movement that is taking magnitude. It is a divergence

between The Searchers and A Fistful of Dollars.

Since, A Fistful of Dollars is an Italian film, the civil

rights movement did not preoccupy its director, Sergio Leone, as much as it

preoccupied John Ford. American filmmakers transposed, in the old west, the

questions that trouble them in contemporary times. In The Searchers,

John Ford does not hide the disdain of Ethan Edwards toward the Native

Americans, or toward the women who had been captured by Native Americans. For Ethan,

these women “ain’t white… anymore. [They are] Comanche[s]” (Ford 1:15:40). This

also applies to his captured niece, Debbie, who he has promised to find. Ford

reverses the expectations regarding his hero. Ethan is not the chivalrous

figure common to so many western films in which the hero searches for a “damsel

in distress” to deliver. There is a sense that if he finds Debbie, he will kill

her. And indeed, that is what Martin fears when he says to Laurie, “It is what

I am afraid of Laurie, [Ethan] finding her” (Ford 52:05). To Ethan, a woman captured

by Native Americans is dead. When he writes his testament, leaving as sole

beneficiary Martin, his adopted “half-breed” nephew, he does not forget to

mention that he is “without any blood kin” (Ford 1:30:57). To him, the Debbie

that he knew as a little girl and to whom he gave his confederate army medal is

dead. In his racist endeavors, Ethan’s methods are as violently irrational as

the methods of the Comanche. He desecrates bodies twice. The first time is when

he shoots a dead Comanche’s eyes. Scorned by his comrades, he simply retorts

without eyes “[the Comanche] has to wander forever between the winds” (Ford

00:26:51). The second time, he scalps Scar, the Comanche warrior who killed his

family and captured Debbie; the scalping refers to the treatment suffered by

Martha, Ethan’s sister-in-law (Ford 1:55:14). Through how Ethan’s racism is

characterized in The Searchers, the portrait of the hero

defending the community, the myth of the community created by “brave” settlers

is shaken. Settlers such as Ethan become more savage than the savageness they claim

to tame (Eckstein 18).

It is not only the violence of Ethan and Joe that

innovates modern westerns but the moral ambiguity of their motivations that is ground-breaking.

According to Philip French, “the hero is the embodiment of good, […] [he]

respects the law, the flag, women, and children […] he uses bullet and words

with equals care, is a disinterested upholder of justice and uninterested in

personal gain. He always wins” (French 48). Yet both characters do not follow

those principles. Ethan does not respect the law. It is implied by Ford that

the protagonist is wanted in the North for bank robberies he committed. Indeed,

Ethan always carries on him “Yankee” gold coins, and he makes it clear to the

sheriff that his only allegiance is to the Confederate States of America (Ford

00:11:59-00:12:31), despite the film is set in 1868, three years after the

American Civil War. Ethan and Joe do not “use bullet and words with equals

care”, they speak only when necessary, and let guns do most of the talking. Regarding

charity, it is hard to argue that the characters are “uninterested in personal

gain” (French 48). Ethan’s motivation is to kill Debbie, he searches for Scar

to avenge his family and his sister-in-law. It is implied by Martha and Ethan’s

kiss, and her caressing his confederate cloak, that they have an illicit love

affair (Ford 00:13:18). When Ethan comes back to the ruins, left by the

Comanches, of his brother’s home, he only seems to care about Martha. Him

holding Debbie, looking her in the eyes, and deciding to spare her has not much

to do with a sudden redemption. In the conflict that opposes his hate of

Comanche to his adulterous love for Martha, he chooses to save the last memory

that Martha had left him before dying, her daughter. In summary, Ethan’s

“heroic” actions are not motivated by the altruism of traditional western

heroes, but by his impulses and desires. Joe’s good deeds also find their

source in unheroic goals. The town in which he finds himself is crooked by two

bandit gangs. When he learns that fact, he says, “There’s money to be

made in a place like this” (Leone 00:12:34). He does not care

about the perpetual violence that reigns in the town. As the title suggests, he

is only interested in making a “Fistful of Dollars”. His methods for acquiring

these profits are as treacherous as the villains’. For example, he fabricates a

piece of information that he sells to both rival gangs for five hundred

dollars. In the end, unlike Ethan, he finds a semblance of redemption; he saves

a holy family, Marisol, and Jesus, from the claws of one of the gangs.

Nevertheless, just like Ethan, once the peace is re-established, he is unfit to

live in the society that he defended. Both are loners. Ethan was first a

warrior, a soldier who has lost his purpose in times of peace, he has a

savageness that scares his own family. As Sue Matheson suggests, “He cannot be

purified because, for him, the war has not ended” (Matheson 206). This is why

at the end of the film, in the famous doorway scene, as the lyrics of the

closing song suggest, he just “ride[s] away” (Ford 1:58:04). As for Joe, he

also rides away into the unknown, he says that he cannot remain in a frontier

village where he will be caught the middle of the Mexican armies and the United

States armies. But, he never wanted to stay, “[Leone’s] heroes and villains are

not the pioneers of a new west, but [its] temporary leaseholders” (Frayling

189). In this way, Ethan and Joe have of eclipsing themselves when the issue at

the center of the film is resolved, they share similarities with traditional

western heroes, except that they are not the embodiment of good. Ethan and Joe,

both metaphorically and literally do not wear white hats. They quit the

civilization because their violence is the next threat to the community not

because they are metaphorical angels; they could be the villain in other films.

In summary, Ethan and Joe differentiate themselves from earlier forms of western protagonists because they are not traditional heroes since they are hateful, violent, and self-interested. Myths helped bound communities together, but they often overlooked the vices of reality. Ethan and Joe represent these vices that society has denied. They highlight the idea that communities were not created by principled heroes, but instead by men of action who often did not have the best of motivations. As they say in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” (Ford 1:59:41-1:59:48).

Works

Cited

Eckstein, Arthur M. “Darkening Ethan: John

Ford’s ‘The Searchers’ (1956) from Novel to Screenplay to Screen.” Cinema

Journal, vol. 38, no. 1, 1998, pp. 3–24. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1225733. Accessed 7 Feb. 2023.

Ford, John, director. The

Searchers. Warner Bros., 1956.

Ford, John, director. The

Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Paramount Pictures, 1962.

Frayling, Christopher. Spaghetti

Westerns. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

French, Philip. Westerns.

Secker and Warburg, 1973.

Leone, Sergio, director. A

Fistful of Dollars. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1964.

Matheson, Sue. The Westerns

and War Films of John Ford. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Commentaires

Publier un commentaire